The first time I encountered an underwater world was when I was seven years old. My interest was not piqued by the huge and mysterious ocean; that would happen later. Instead, my attention was captured by a perfect miniature mangrove ecosystem that was hidden in a corner of the Florida Aquarium. It fascinated me how I could wrap my arms around the tank and become submerged into this world less universe. While my peers pressed their faces against the shark tank glass, I chose to focus on a small universe surrounded by walls.

My passion for aquariums turned out to be more than a fleeting fancy. By the time I returned home on that day, I had become convinced that I one day wanted to have an aquarium of my own. Since I already had a piggy bank, I decided not to waste time. That night turned out to be special, as I counted a total of $27.43 laid out on my bedroom floor.

My mother still chuckles when she thinks of how self assured I was when I walked down to the local pet store and bought a bunch of goldfish with literally no idea of how to actually run an aquarium. And while I was lucky enough to walk out with a plastic tank and guppies, the terrible reality of not understanding the basics of what it took to run an aquarium turned the entire balanceable ecosystem within weeks into an algae-filled, murky tomb with no visibility.

Living next to the coast of Florida provided me with the perfect playground for my brewing fascination. My family’s house was a few miles from the Gulf, and during weekends, I would skim through tide pools trying to catch specimens with mason jars and fill notebooks with detailed observations. My room slowly became what my father coined “the laboratory”—an assorted collection of every tank, pump, and test kit that made absolute sense to me but useless to anyone else. By the age of twelve, I was ready to explain, in excruciating detail, the parameters and cycles of water and nitrogen as my science teacher expected, leading him to both want to promote me to higher classes and gently guide me into spending time with a wider array of interests.

When I was thirteen, I got it into my head that I could recreate a Florida tide pool in our guest tub, so not all of my experiments were kept in my room. For weeks on end, I would collect water, small critters, sand, and rocks. And for almost a week, the system worked flawlessly until it spectacularly broke down, flooding our house with several bewildered crustaceans, saltwater and sand. The repairs ended up costing more than my dad’s monthly salary and the extensive punishment that followed was equally epic and imaginative. All recreational activities involving water in the house were strictly forbidden.

When I turned fourteen, my father walked me to the garage where a custom-built 55 gallon fish tank was waiting on a stand as a gift. “If you’re going to flood the house,” he said while handing me a professional water test kit, “at least do it right.” Even now, that gift remains one of the most thoughtful presents I received in my life since it upheld an essential part of my identity.

While my classmates were struggling with social politics and sports, I was perfecting the growth of useful bacteria and plant life, both above and below water. After correcting my employer’s advice regarding the compatibility of cichlids, he offered me a role at the local pet store which was bound to happen eventually. At seventeen, I was in charge of the freshwater section and thanks to my reputation, I was known as “that fish kid” by most local enthusiasts.

Marine biology became my major at the University of Miami, and soon enough, my dorm room earned a rather dubious distinction for having three tanks, despite rules banning even one. My roommate Trevor, who was doing business, used to grumble about the filter noise and late-night water changes. I remember vividly, three weeks into our first semester, I saw him checking the pH levels in my community tank. By the time we went home for the holidays, he already had his own nano reef system set up. Despite all this, we remain friends, although he maintains I’ve single-handedly ruined his life for showing him “the world’s most expensive hobby.”

My methodical nature was satisfied with academic life, but I found the traditional routes of research too restricting. While some professors tried corralling me into studying the decline in coral reefs or fishery management, my area of interest remained in controlled ecosystems. The closed systems nutrient cycling thesis I did in my last year seemed to surprise faculty members, but it did get me a job at the aquarium where it all started.

My former position as an aquarist for the tropical exhibits division of the Florida Aquarium humbled me over the course of three years. Working with massive systems made it so mistakes were not measured in the death of a few fish, but rather in the thousands of dollars worth of public damage that could be caused. I had to adapt to systems thinking and consider all potential consequences as well as appreciate the balance that maintains ecosystems and prevents catastrophic crashes.

My career took an unexpected turn after the visit from the Japanese aquascaper. The man spent a week building our Southeast Asian biotope display. I observed as not only did he perform a reconstructive surgery, healthcare style, but control and power over art and nature blended into one, changing scientifically accurate boring tanks into awe inspiring underwater jungles. In addition, he used the identical species of vegetation that we had been cultivating. This was not mere recreation, but interpretive art that managed to portray untouched landscapes in a manner that surpassed our literal efforts.

From Takashi Amano’s minimalist Japanese nature aquariums to the Dutch planted tanks with their careful consideration of colors and texture, I studied every aquascaping style for an entire year. I transformed my apartment into a testing ground, each tank exploring different techniques with specialized tools, premium hardscape materials, and specialized plants. I indulged in purchasing incredibly expensive rare plants and premium hardscape materials despite my modest salary. I spent an absurd amount of my earnings and it was astonishing to think that creating natural looking environments requires truly, deeply unnatural levels of control.

When my home tanks gained attention in online forums, my break came through early social media. What began as casual weekend design consultations gradually progressed to becoming a sustainable career. After a well-known aquarium magazine sensationalized my design of a paludarium with dart frogs above and cardinal tetras below—half land and half aquatic—I received enough attention to consider quitting my stable job in the aquarium industry and pursuing self-employment.

That transition taught me that knowing how to do something does not mean that someone understands business related to it. My first year running my aquascaping consultation business was the epitome of a ‘learn the hard way’ crash course, complete with a side of ramen noodles. I made overly ambitious mistakes, like charging way too low for my services and working even harder to somehow manage all of my tasks. I would also create one of a kind, eye-catching tanks branded as “works of art,” such as the waiting room fish tank for a particular doctor’s office that was filled with confrontational fish hell-bent on defending their territory rightfully positioned near a child’s eye-level. The physician was gracious, the poor traumatized four-year-old needing post-fish-attack-vision-recovery therapy, not so much.

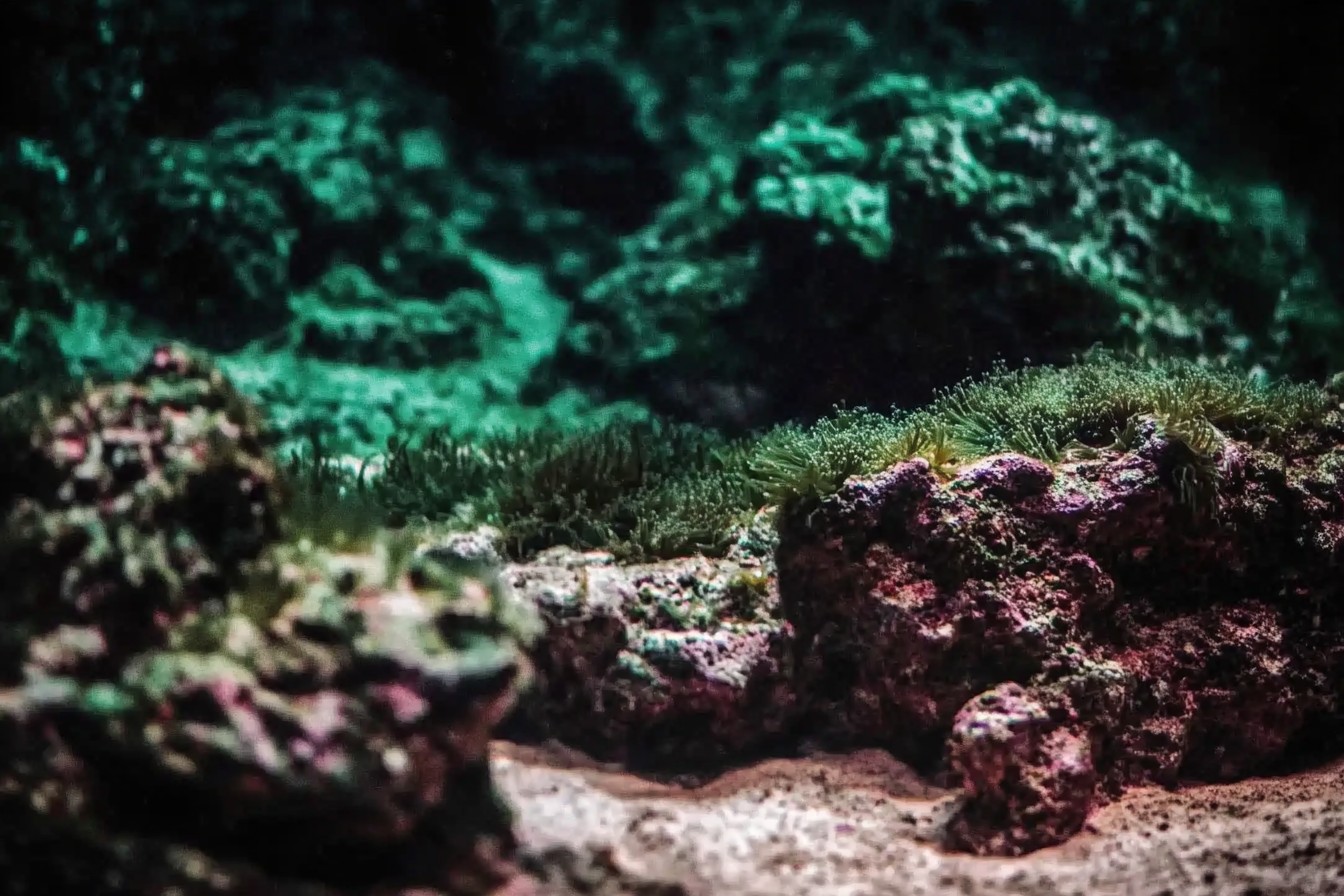

To this day, fifteen years after this episode in my life, my apartment has the pride of place of being the most prominent figure test bed. In terms of space, seven tanks of different styles and sizes take precedence in the room, each symbolizing a distinct style and challenge. The biotope I nurtured to analogous 120 gallons of amazon sprawling waters has run for the heartbeat of six glorious years, emulating gentle seasonal shifts akin to its natural surroundings. The forty gallon pseudo cove serves as my experimental canvas where conventional wisdom gets tested. And the bowl with sapaciously simple decor comprising exclusively of moss and shrimp that rests on my work desk serves as a notion that disorder can often outdo order.

Through my career changes, relationships starting and ending, to moving cities, these tanks have captured my life’s moments. They’ve helped me learn patience and how caring for a being reliant on your routines offers strange solace. The rituals involving aquarium upkeep, like observation, pruning, and shelf rearranging, impose a tempo reminiscent of a slower, less rewarding reality devoid of modern convenience.

The failures have been as insightful as any successes. I remember the thirty pound driftwood chunk that flooded my client’s antique Persian rug after shattering a glass tank. Or the malfunctioning CO2 system during the international competition which filled my meticulously crafted landscape with fog mere minutes before judging. Not to mention the so-called “rare” plants I spent a fortune importing only to see them dissolve even in optimal conditions.

Every failure made me realize something of value — be it about planning for the worst, the natural chaos of systems, or the thin line between confidence and arrogance. Now I incorporate failure as a standard part of my expectations and learn to regard it not as an end, but as vital information. This perspective has proven beneficial far beyond the context of aquariums.

I have always found my utmost joy in assisting novices set up their first successful aquariums. That smile is priceless when they craft a stunning aquascape which sustains diverse life. Each aquarium is filled with masterpieces that offer both a different tale and countless challenges. Often, they reveal something deeply important about control versus letting go. While these glass ecosystems capture our world, they showcase our struggle and deep yearning to dominate nature which can never be fully conquered.