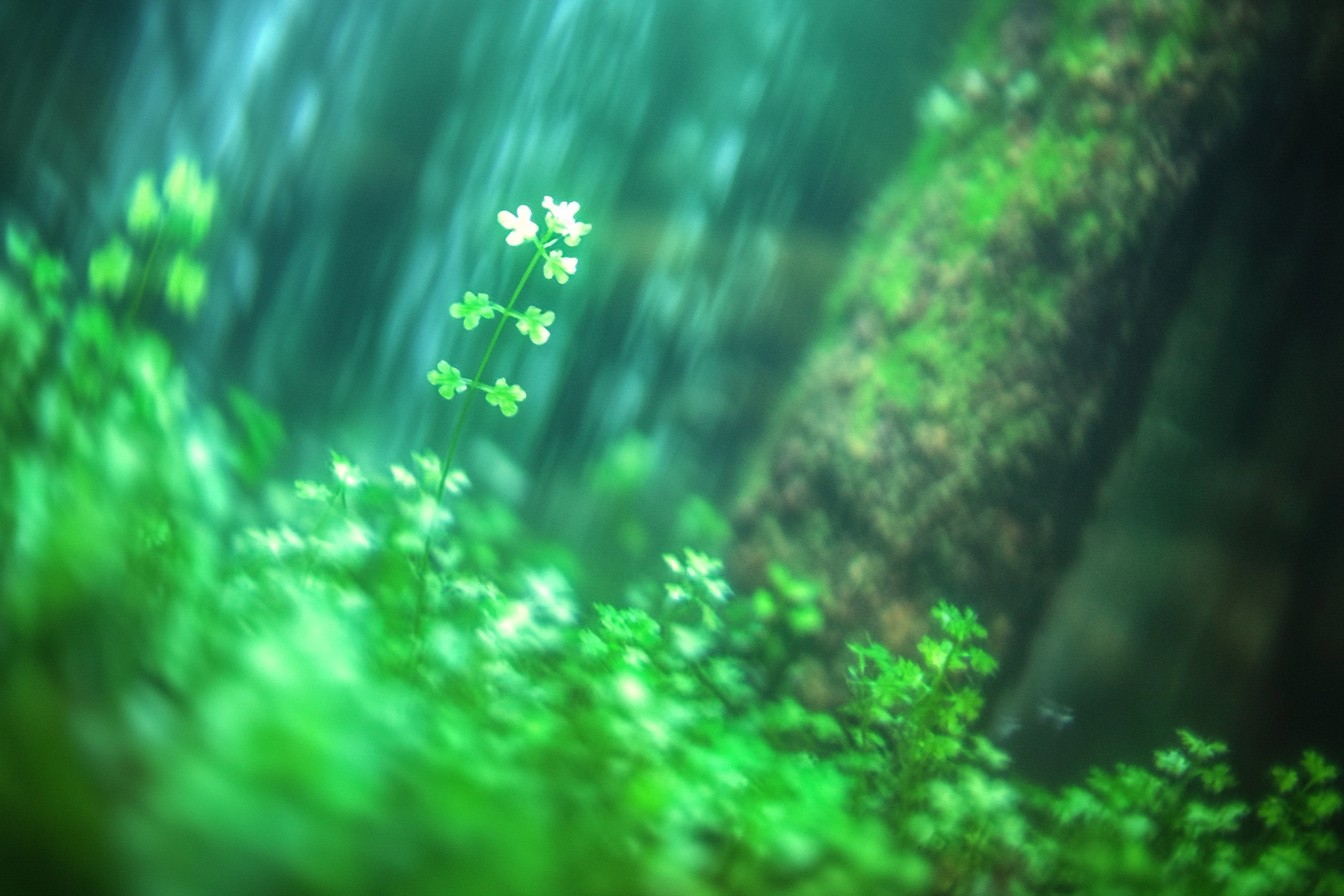

Knowing how to multiply a single plant into multiple plants makes designing an underwater forest easier. After aquascaping for years, going through multiple failures, I have recently come to view propagation, albeit reluctantly, as a form of moving meditation. Being able to watch small tree cuttings grow into little forests able to enhance the charm of an aquarium is something simply magical.

Prior to this I had attempted different ways of self sustaining plant propagation, but my lack of skills caused more issues than they solved. Watching the sorry Bucephalandra variant I had purchased for a steep price staring came to a sudden halt the moment my fingers began trying to plant the specimen, clumsily breaking off a side shoot. After stuffing the broken part into some rocks in a different corner of the tank I opted to forget about it. Months later the astounding me was fortunate enough to spot new growth on a fragment that had been tossed away. The occurrence alone was mesmerizing enough as astounding me, but what stood out even more was my newfound fascination with the endurance and reproductive powers of aquatic plants.

The stem plants pacify even the most concerned of us garderners because of the ease with which they propagate, hence why they tend to dominate planted aquariums.

Rotala, Ludwigia, and Bacopa are species of plants that can easily be propagated and grown at a fast rate simply by taking cuttings. When I entered the commercial aquascaping industry, I had a 20 gallon propagation tank full of stem plants. This type of tank was unique in the sense that I could grew the plants for commercial purposes. I would maintain the growth by taking out the uppermost portions and using them to fill client tanks. After which, I would take the uppermost portion of the lower stem and replant the tops into the substrate. The lower portions would then sprout new side shoots becoming bushier, denser, and taller with every cycle. In a matter of months, I was able to provide several fishes tank installations using only a couple of plants as ssupports.

Stem propagation is much easier than what it seems to be. Timing is everything. Difficulties arise in the form of a stem being cut too early before establishing strong grown leading to challenges for the parent and the cutting. With waiting too long, there is issue from lower portions getting sparse and leggy. With constant observation, developing a rhythm is more than possible. For optimal outcomes, my cutting techniques involved fully grown stems with their capped portion containing roots and uncut leaves at the stem alongside flowering remnants.

Rhizome plants differ radically from the rest.

Anubias, Java Fern, and Bucephalandra have leaves on one side and roots on the other, growing off of a central stem. They are not able to reproduce through simple stem cutting because a stem is required to be shredded. Making an attempt at propagating Anubias was rather intimidating. While doing a bit of “plant surgery” on a specimen I had let fully configure over the course of months, I had to ensure that I was sat on the right side of a risk taking decision. These plants were able to heal the bounds remarkably well. It was shocking to see callous regions sealing in a few days, but to witness new sprouts afterward in only a few weeks was breathtaking. What seemed like a complicated process did, in reality, turn into effortless maintenance.

The most satisfying thing of all was the propagation method I discovered for carpet plants, such as Eleocharis parvula and Micranthemum tweediei. The most difficult part was the starting stage dealing with tissue cultured canisters that only offered, at the very best, a handful of miniature plantlets. These plantlets were arranged in such a way that each of them could be excelled and planted in a grid design. It is very important to ensure that the stems are positioned about one inch apart. With sufficient illumination and optimal CO2, these tiny plants can spread throughout the area and act as a carpet.

Contemplating this phenomenon over a series of weeks—individual plants extending tendrils to clutch their neighbors— it’s remarkable to think I feel like observing an orchestrated endeavor, a form of intelligence burgeon while discovering and controlling new grounds.

If not controlled, some plants, such as Amazon Frogbit and Water Spangles, can drown themselves in their own light. Their reproduction rate is exponentially high, which can lead to destruction rather than good. Through trial and error, I learned to control their unique form of “insanity” by creating floating, dense networks of these plants that grow in nutrient-filled tanks. These plants can further serve as a shadowy aid in water filtering.

My ed Propagation Structures have undergone the most radical transformations over the years. With no clear organizational system in place, my unused windows became makeshift storage areas complete with totes and buckets. Now, I can fully appreciate the effort spent customizing idea specific propagation machines with lighting, filters, and nutrient dosers.

Plants are grown in my terrarium above water level with a substrate fill of saturated humidity. Some delicate species are encouraged to grow above water by using an emersed growth method. In fact, many species are able to grow faster when their roots are in the soil, which is due to an emersed rooting strategy, rendering them easier to be kept in placed tanks.

The most critical factor that underscores the temperature control success for aquaculture is bourne within 24 to 26 degrees celsius, within the lower mark of 75 to 78 celsius degrees. I learnt that combustively hot, or chillingly cold guarantees destruction towards aquatic ecosystem life. To mitigate winter thermal fluctuations that batter my space in a tangled mess of shifting room temperatures, a reliable thermostat coupled with an aquarium heater set to above optimal temperatures would sustain success.

This expansion within my pre-existing venture defined what other elements of the process I could control, thus basic air powered sponge filtration along with LED shop lights could be streamlined into these modular robotic propagation racks made from low-cost plastic tubing. For restocking purposes, I incorporated converting upstairs bedrooms into greenhouses which my other housemates did not care for as it cut down our living expenses.

My business was not a fully functioning venture, it was just profit aquaculture.

Buying bulk plants from vendors, to me, was a remorseless repetitive process. However, I could make a single purchase of a specimen and propagate endless amounts of plants. A singular investment of fifty dollars on tissue-cultured carpet plants could, within half a year, generate thousands of dollars worth landscaping materials. Moreover, this approach was more economical and afforded me complete control over the health and quality of the plants meant for client installations. The headache of bringing in snails and algae from supplier stock was now nonexistent since all the plants were produced in my environment.

Apart from the furthering productivity, propagation deepened my understanding of my craft and the materials that I work with. Involvement with the reproductive aspects of these plants – their growth patterns, preferred environments, and astonishing regenerative abilities – required me to have some sort of design intuitive foresight as to how they would react at different stages of an arrangement. This newfound understanding influenced how I practiced aquascaping. I stopped regarding plants as passive inert constituents of a design. Instead, I began appreciating their everlasting growth and change as vital to artistic expression.

For those pursuing their own journeys in propagation, I recommend starting out with some easier species like Water Wisteria (Hygrophila difformis) or Java Moss (Taxiphyllum barbieri). These species will often offer quick wins, as they will be able to propagate relatively easily under less than optimal conditions, boosting the confidence necessary to attempt more challenging species.

Patience. That would be the one thing that any person can claim to have, in regard to plant propagation. Some of them take weeks, or even months, to show any progress after being cut or divided.

It is safe to say that after years of experience on reproduction, I now consider these plants as allies instead of mere capital. Every species has certain unique traits like different modes of reproducing and time intervals. From my perspective, the working boundaries are far more rewarding than attempting to follow a timetable. For professionals in aquascaping, having the right knowledge about propagation comes with financial gain and a more rewarding encounter with a true living work of art. As we shift from considering each stem as an individual and the aquascape as an underwater forest, the field of plant propagation is offering us deeper knowledge and understanding along with aesthetic value.